MONTHLY BLOG 24, HISTORY AS THE STAPLE OF A CIVIC EDUCATION

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2012)

Politicians have a duty to attend to civics as well as to economics. Indeed, we all do. So talking about whether the study of History is ‘useful’ for the economy is a very partial way of approaching an essential component of human’s collective living. We all need to be rooted in space and time. Politicians should therefore be advocating the study of History as the essential contribution to individual and social connectedness. In a word, civics in the full meaning of the term. Not just learning how to fill in a ballot paper – but learning how communities develop over time, how they cope with conflict and with conflict-resolution, and, incidentally, how they struggle to create truly fair and democratic societies.

Praise of the study of History as a means of learning essential skills is all very well. Lots of useful things are indeed achieved by this means. People learn to evaluate complex sources, to make and debate critical judgments based upon careful assessments of often contradictory evidence, and to understand continuity and change over the long term. So far, so good.

Yet it is seriously inadequate to recommend a subject only in terms of the skills it teaches and not in terms of its core content. It’s like (say) recommending learning to sing in order to strengthen the vocal chords and to improve lung capacity. Or (as the ad agency Saatchi & Saatchi notoriously did in 1988) recommending a visit to the Victoria & Albert Museum in order to enjoy a nice egg salad in its ‘ace caff’ – with some very valuable art objects attached.

By the way, so notorious has that advertisement become that it is strangely difficult to find the originals image on the web. It seems to have been self-censored by both the Museum and the ad agency – probably in shame.

By the way, so notorious has that advertisement become that it is strangely difficult to find the originals image on the web. It seems to have been self-censored by both the Museum and the ad agency – probably in shame.

When recommending History, there is a crucial Knowledge agenda at stake as well as a supporting Skills agenda. Of course, the two are inextricably linked. Historical skills without historical Knowledge are poorly learned and quickly forgotten. But learning History has a greater and essential value purely in its own right. It is not ‘just’ a route to Skills but a subject of all-encompassing and thrilling importance.

All of human life is there; and all humans need access to this shared reservoir of knowledge about our shared past. People always glean some outline information by one means or another. They pick up myths and assumptions and bits and pieces from their families and communities.

But people learn more and better when they learn systematically: about the history of the country that they live in; and about the comparative history of other countries, both nearby and far away; and about how a myriad of different developments around the world fit into a long-term human history, which includes continuities as well as change.

Needless to say, these perceptions are hardly new. ‘Histories make men wise’, as Francis Bacon long ago observed. Thinkers and doers from classical Greece to Winston Churchill have agreed and recommended its study.

Why then has the subject matter of History been comparatively undervalued in recent years? It can’t just be the power of the Skills agenda and the influence of ministers fussing about every subject’s contribution to the economy.

Why then has the subject matter of History been comparatively undervalued in recent years? It can’t just be the power of the Skills agenda and the influence of ministers fussing about every subject’s contribution to the economy.

Nor can it be that History teachers are ‘boring’ and that they teach students nothing but the dates of kings, queens and battles. Ofsted report after Ofsted report has stated otherwise. The subject is considered to be generally well and imaginatively conveyed. Moreover, the sizeable number of students choosing to take the subject, even once it has ceased to be compulsory, shows that there is a continuing human urge to understand the human past.

Nonetheless, the public reputation of History as a subject of study is currently poor. It is often dismissed as the ‘dead past’. Why should students need to know about things that have long gone? The pace of technological change in particular seems to point people ‘onwards’, not backwards. What can the experience of the older generation, who notoriously have trouble coping with shiny new gadgets, teach the adept and adaptable young?

Well, there are many answers to such rhetoric.

In the first place, things that are ‘dead’ are not necessarily lacking in interest. It is valuable to stretch the mind to learn about vanished cultures, as some indeed have. Impressively, archaeologists, historians, palaeontologists, biologists and language experts have together discovered much about the long evolution of our own species – often from the skimpiest bits of evidence. It’s a highly relevant story about adaptation and survival, often in hostile climes.

Meanwhile, there is a second answer too. It’s completely fallacious to assume that everything in the past is ‘dead’. Much – very much – survives and develops through time, to create a living history, which embraces everyone alive today. The human genome, for example, is an evolving inheritance from the past. So are the dynamic histories, languages and cultures that we have so variously created.

We need more long-term accounts of how such things continue, evolve and change over the very long term. The recent stress by historians upon close focus studies, looking at one period or great event in depth, has been fruitful. Yet it should not exclude long-term narratives. They help to frame the details and to fit the immediate complexities into bigger pictures. (My own suggestion for a secondary-schools course on ‘The Peopling of Britain’, in which everyone living in Britain has a stake, is published in the November issue of History Today).1 In sum, we all need to learn systematically – and to continue learning – about our own and other people’s histories. It’s a lifetime project, for individuals and for citizens.

• My December Blog will consider further how historians can advance the public case for studying History.

1 P.J. Corfield, ‘Our Island Stories – The Peopling of Britain’, History Today, vol. 62, issue 11 (Nov. 2012), pp. 52-3.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 24 please click here

Did the ancient University really lack trust in its own staff and its invited external examiner? In this case, common sense prevailed; and, after a protest, the instruction was withdrawn.

Did the ancient University really lack trust in its own staff and its invited external examiner? In this case, common sense prevailed; and, after a protest, the instruction was withdrawn.

Unfairness is written into the proposed contract from the start, by asking the elected members to attend a specified percentage of all public meetings in their constituencies. Those whose political patches contain many residents’ associations, neighbourhood watches, and other local gatherings will be required to jump over a much higher hurdle than those in sleepy Clochemerles, where nothing happens.

Unfairness is written into the proposed contract from the start, by asking the elected members to attend a specified percentage of all public meetings in their constituencies. Those whose political patches contain many residents’ associations, neighbourhood watches, and other local gatherings will be required to jump over a much higher hurdle than those in sleepy Clochemerles, where nothing happens.

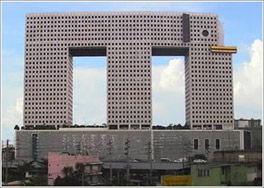

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital.

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital. But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality.

But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality. • A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

• A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.

However, the authorities needed – and still need – to strike a balance. On the one hand, they had to restore civil peace. On the other hand, it’s always wise not to provoke more people to join the mayhem. The use of troops today remains a reserve power. But riot control, in a democracy, is essentially viewed as a task for policing – and, ultimately, for community self-control.

For that reason, David Cameron’s slogan enrages many people, not only on the centre and left in politics, but also on the Thatcherite right, who prefer individualist rather than communal alternatives to the state. In addition, plenty of non-political grass-roots activists dislike the term too. It appears as though a currently powerful section of one political party is trying to ‘own’ the countless manifestations of community life.2

For that reason, David Cameron’s slogan enrages many people, not only on the centre and left in politics, but also on the Thatcherite right, who prefer individualist rather than communal alternatives to the state. In addition, plenty of non-political grass-roots activists dislike the term too. It appears as though a currently powerful section of one political party is trying to ‘own’ the countless manifestations of community life.2 But organic expressions of civil society began long before David Cameron invoked the ‘Big Society’ to purge the Tory’s anti-society image and will continue long after the current government has disappeared.3

But organic expressions of civil society began long before David Cameron invoked the ‘Big Society’ to purge the Tory’s anti-society image and will continue long after the current government has disappeared.3 Secondly: the pre-committed research framework. Programmes should not start by ruling out all the research options. In this case, it cannot be taken for granted that ‘the’ central state is ‘the’ problem for those seeking to build communities. Governments in contemporary societies are very variegated and diverse in their roles and structures. Their impact can in some circumstances be inimical or discouraging to community activism.

Secondly: the pre-committed research framework. Programmes should not start by ruling out all the research options. In this case, it cannot be taken for granted that ‘the’ central state is ‘the’ problem for those seeking to build communities. Governments in contemporary societies are very variegated and diverse in their roles and structures. Their impact can in some circumstances be inimical or discouraging to community activism. But it didn’t work. Long before Lysenko’s teachings were officially discredited as fraudulent in 1964, they were sidelined in practice. In wartime, Stalin learned the hard way that he had to trust his generals to fight the war. Yet he did not get the message in science, or indeed in other subjects, like history, where he intervened to support one argument as Marxist orthodoxy against another as ‘bourgeois’ revisionism. Between them, Stalin and Lysenko halted Russian biological studies and palpably harmed Soviet agriculture for over a generation, greatly weakening Soviet Russia as an international power.4

But it didn’t work. Long before Lysenko’s teachings were officially discredited as fraudulent in 1964, they were sidelined in practice. In wartime, Stalin learned the hard way that he had to trust his generals to fight the war. Yet he did not get the message in science, or indeed in other subjects, like history, where he intervened to support one argument as Marxist orthodoxy against another as ‘bourgeois’ revisionism. Between them, Stalin and Lysenko halted Russian biological studies and palpably harmed Soviet agriculture for over a generation, greatly weakening Soviet Russia as an international power.4 As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration.

As the sorry tale of FIFA currently implies, oligarchies without external audit and accountability sooner or later get corrupted. So there was a serious principle as well as praxis behind the late Labour Government’s extension of the audit culture to so many aspects of public administration. Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

Alternatively, the quest for measured information can insensibly become itself a substitute for effective management. The false impression is gained that managers can organise everything if only they have a large enough database. That way, vast sums of money are wasted only to find that giant systems don’t work.

In fact, the reality is different in many ways. The tertiary sector is very variegated. It has faults, but they are often too neo-brutally managerialist rather than slumberingly Porterhousian.

In fact, the reality is different in many ways. The tertiary sector is very variegated. It has faults, but they are often too neo-brutally managerialist rather than slumberingly Porterhousian.

Divisions between Universities are now institutionalised into rival lobby organisations. The Russell Group (founded 1994) represents 20 Universities, self-defined as the research elite, constituting a limited company (no: 6086902), operating from a base in Cambridge. Feeling excluded, another 19 smaller research institutions created the 1994 Group to defend their research credentials. It operates with an Executive Board, chaired by an academic, with at least five permanent staff members. A similar corporate structure services the University Alliance, which represents 23 ‘major business-focused’ Universities. And from 1997 onwards the Campaign for Mainstream Universities (CMU) has organised 27 former Polytechnics and University colleges – then known as ‘new’ Universities although many already had long histories. This group now operates as a London-based Think-tank, known as the Million+ Group. These divisions mark a classic case of self-divide and be ruled.

Divisions between Universities are now institutionalised into rival lobby organisations. The Russell Group (founded 1994) represents 20 Universities, self-defined as the research elite, constituting a limited company (no: 6086902), operating from a base in Cambridge. Feeling excluded, another 19 smaller research institutions created the 1994 Group to defend their research credentials. It operates with an Executive Board, chaired by an academic, with at least five permanent staff members. A similar corporate structure services the University Alliance, which represents 23 ‘major business-focused’ Universities. And from 1997 onwards the Campaign for Mainstream Universities (CMU) has organised 27 former Polytechnics and University colleges – then known as ‘new’ Universities although many already had long histories. This group now operates as a London-based Think-tank, known as the Million+ Group. These divisions mark a classic case of self-divide and be ruled.