MONTHLY BLOG 50, WHAT DOES THE ‘TEMPORAL TURN’ MEAN IN PRACTICE – FOR HISTORIANS AND NON-HISTORIANS ALIKE?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2015)

The senior American policy-maker, who claimed in 2004 that: ‘When we act, we create our own reality’,1 proved to be dangerously wrong – in Iraq as elsewhere across the world. Instead, it is history which provides the past and present reality. Hence the need to understand everything in its full historical context. That’s what the Temporal Turn2 really means: a turn to Time, whose effects are studied by historians, alongside the practitioners of many other long-span subjects, like archaeologists, astrophysicists, biologists, climatologists, geologists, or zoologists.

Paying fresh attention to Time calls for greater changes in the mind-set of non-historians than it does for historians. For us, it’s axiomatic that History deals with the very long term. But for other disciplines, it means making a fresh effort to ‘think long’. To reflect that the current parameters of your discipline may not remain the same for ever. To become aware of change and historical context, as an integral component, not just an add-on extra. But also to be aware of deep continuities, which may not be amenable to policies of instant reformation. Thus the Temporal Turn will encourage an intellectual shift in many disciplines across the board in the Arts, Social Sciences and Sciences, just as the Linguistic (or structural) Turn, as announced by Richard Rorty in 1967,3 affected philosophy (his prime target) as well as anthropology, social studies, theology, ethics, literary studies, and even, to an extent, history.4

Historians are debating quite what the Temporal Turn means for them too. Crusading zeal on behalf of the discipline, as expressed in the recent History Manifesto, makes for good copy and rousing appeals. Thus Jo Guldi and David Armitage end their polemical tract with a Marxist echo: ‘Historians of the world unite! There is a world to win – before it’s too late’.5 Yet some of the early responses from fellow historians are unexcited. In effect, they are saying that public history has already arrived: ‘We do this already’. In particular, Deborah Cohen and Peter Mandler criticise The History Manifesto for being wrong both in its descriptions and its prescriptions: ‘Historians aren’t soldiers, they don’t fight on a single front, and … they certainly don’t need to be led in one direction’.6 Cohen and Mandler specifically dislike Guldi and Armitage’s hopes that public policy debates can be resolved, or at very least enlightened, by using ‘big data’, derived from massive long-span historical databases. Instead, they stress creative diversity within the discipline.

Who is right in this disagreement? In one sense, Cohen and Mandler are sure to be correct, in that historians can’t be told what to do and how to do it. Their subject is already hugely diversified; and, unlike many academic subjects, it overlaps with a huge semi- and non-academic world of freelance historians and do-it-yourself amateurs. This massive collective project, which has been developed over centuries, is not for speedy turning.

|

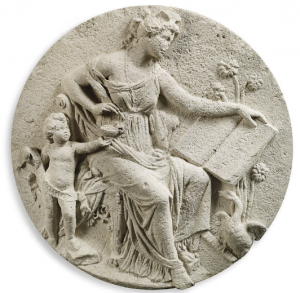

Clio, Goddess of History, c1770: in Portland stone roundel (32in diameter), from Plas Llangoedmor, Cardigan, Wales. Source: http://www.ausbcomp.com/~bbott/wortman/Clio_Goddess-of-History.htm. |

On the other hand, The History Manifesto is importantly right in its general message, even if not necessarily in its specific preferences. It is one sign among many of the intellectual shift towards long-term analysis and away from short-termism. Urgent contemporary issues – like the search for long-term economic growth, or the challenge of resisting/coping with climate change – have long-term roots and demand a long-span historical perspective in response. Historians should be primed and ready to contribute. Indeed, more. Where necessary, historians themselves should be recasting the debates and the big questions.

That contribution can be done on the strength of insights and analysis from micro-history as well as from macro-history. The Temporal Turn does not mean that everyone must study millennia. There are virtues in short-term probes and in long-span narratives – and in the many way-stations in between. The length of periods studied should be dictated only by the research questions in play, as mediated by the source materials available.

Nonetheless, historians of all stripes should be ready to explain or at least to speculate on the bigger picture(s) revealed by their research. When asked something sweeping, it’s not enough to reply: ‘I’m sorry. It’s not my period’. Who other than historians are better placed to comment on historical trends? And there are plenty of ways in which attention to the diachronic can be strengthened in current History research and teaching – of which more in a future BLOG.

|

Chinese figurine of Shou Lao or ‘Old Longevity’, representing the power of Time. Since he carries the scroll which records everyone’s date of death, his good favour is auspicious. Source: www.daodoctor.com. |

Immediately, three longitudinal insights from History are worth highlighting. (1) Covert change: there are aspects of behaviour, which people often consider to be permanently part of the human condition, which may not really be so. (2) Covert continuity: there are big crises and upheavals in history, which people often think of as ‘changing everything’, but which don’t necessarily do so. And, as a result, (3) change over time is much more than a simple binary process. People often entertain very schematic ideas of the past. Before a certain date, everyone did X, whereas after that time, no-one did. In fact, there are multiple turning points, not always in synchronisation.

Long-term change can be insidious and gradual as well as turbulent and rapid. It is halted by continuity and yet hastened by revolutions. History is interestingly complex – but not inexplicable. Ask the historians; and, historians, tell the world.

1 Attributed to Karl Rove, George Bush’s Deputy Chief of Staff (2004-7). See M. Danner, ‘Words in a Time of War: On Rhetoric, Truth and Power’, in A. Szántó (ed.), What Orwell Didn’t Know: Propaganda and the New Face of American Politics (New York, 2007), p. 17.

2 See PJC, ‘What on Earth is the Temporal Turn and Why is it Happening Now?’ Monthly BLOG/49 (Jan. 2015), for which see https://www.penelopejcorfield.com.Monthly-Blogs.

3 R. Rorty (ed.), The Linguistic Turn: Recent Essays in Philosophical Method (Chicago, 1967).

4 G.M. Spiegel, Practising History: New Directions in Historical Writing after the Linguistic Turn (New York, 2005).

5 J. Guldi and D. Armitage, The History Manifesto (Cambridge, 2014), p. 126.

6 D. Cohen and P. Mandler, ‘The History Manifesto: A Critique’ for American Historical Review, at http://www.deborahacohen.com/profile/?q=content/critique-history-manifesto, opening paragraph

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 50 please click here