MONTHLY BLOG 33, CONTRACTING OUT SERVICES IS KILLING REPRESENTATIVE DEMOCRACY

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2013)

‘Contracting out’ is a policy mantra especially of financial/services capitalism (as opposed to industrial capitalism or landowner capitalism), which has been gaining greater support year by year. As an ideal, it was succinctly formulated by Nicholas Ridley (1929-93), who held various ministerial posts under Margaret Thatcher government. Theoretically, he hated government expenditure of all kinds: ‘I was against all but the most minimal use of the taxpayer’s purse’.1

For Ridley – himself from a titled family with business interests in ship-owning – the ideal form of local democracy would be one in which the Councillors met no more than once yearly. At the annual meeting, they should set the rate and agree the fees for contracting out municipal services. Then they could all go home. His was an extreme version of what is known in political theory as a preference for the minimal ‘night-watchman state’.2

No mention from Ridley of Town Hall debates as providing a sounding-board for local opinion. No mention of community identity and pride in collective institutions. No mention of a proper scope for in-house services. No mention of elected control of key tasks, including regulatory and quasi-judicial functions. No mention even of scrutinising the contracted-out services. No mention therefore of accountability.

No mention from Ridley of Town Hall debates as providing a sounding-board for local opinion. No mention of community identity and pride in collective institutions. No mention of a proper scope for in-house services. No mention of elected control of key tasks, including regulatory and quasi-judicial functions. No mention even of scrutinising the contracted-out services. No mention therefore of accountability.

Above all, no mention from Ridley of what Edmund Burke called the ‘little platoons’3 (‘local platoons’ would have been better, as their sizes are variable) that bridge between private individuals and the central state. Hence no mention of representative democracy at a local level. This was aristocratic disdain worthy of Marie Antoinette before the French Revolution. Moreover, without representative politics at all levels of society, then popular democracy will, when provoked, burst through into direct action. Often, though not invariably, in an uncoordinated and violent manner.

France, in fact, provides an excellent historical example of the eventual follies of contracting out. The absolute monarchs before 1789 presided over a weak central bureaucracy. As a result, one of the key functions of the state, the collection of taxes, was ‘farmed out’, in the jargon of the eighteenth century. The Ferme Générale undertook the humdrum tasks of administration, absorbing the risks of fluctuating returns, while assuring the monarchy of a regular income. And, to be sure, this system survived for many years. Nonetheless, the French monarchy faced chronic financial problems by the later eighteenth century. And the great political problem was that all the tax profits went to the Tax Farmers, while popular hatred at high payments and harsh collection methods remained directed at the kings.4

In twenty-first century Britain, something of the same situation is developing. The state still has to provide basic services; and remains the guarantor of last resort, if and when private service firms fail. Thus the faults of the system are still the government’s faults, while the profits go to private companies. The other long-term costs are borne by the general public, left to face cut-to-the-bone services, provided by poorly-paid and demoralised casual labour. No-one is popular, in such a system. But the secretive and unaccountable world of the private providers, sheltered by commercial ‘secrecy’, saves them for a while from the wrath to come.

One notorious example is known to everyone. It occurred in July 2012, just before the start of the Olympic Games. The private firm G4S promised but failed to deliver security. The contract was worth £284 million. Two weeks before the opening ceremony, the same role was transferred to the publicly-funded army. It did the task well, to tremendous applause. G4S forfeited £88 million for its failure on this part of the contract.5 Yet, despite this ‘humiliating shambles’ in the words of its chief executive, who resigned just over six months later with a huge payoff,6 the firm remains a major player in the world of security services.

So G4S today advertises itself as ‘the world’s leading international security solutions group, which specialises in secure outsourcing in countries and sectors where security and safety risks are considered a strategic threat’.7 No mention of regular overview and scrutiny, because there is none. It’s another of those businesses which are considered (wrongly, in practice) as ‘too big to fail’. The point of scrutiny comes only after an embarrassing failure or at the renewal of the contract, when nervous governments, having invested their prestige and money in privatisation programmes, don’t care or dare to rethink their strategy. In August 2013, G4S is being investigated by the Ministry of Justice for alleged over-charging on electronic ‘tagging’ schemes for offenders.8 Yet, alas, this costly imbroglio is unlikely to halt the firm’s commercial advance for long.

So G4S today advertises itself as ‘the world’s leading international security solutions group, which specialises in secure outsourcing in countries and sectors where security and safety risks are considered a strategic threat’.7 No mention of regular overview and scrutiny, because there is none. It’s another of those businesses which are considered (wrongly, in practice) as ‘too big to fail’. The point of scrutiny comes only after an embarrassing failure or at the renewal of the contract, when nervous governments, having invested their prestige and money in privatisation programmes, don’t care or dare to rethink their strategy. In August 2013, G4S is being investigated by the Ministry of Justice for alleged over-charging on electronic ‘tagging’ schemes for offenders.8 Yet, alas, this costly imbroglio is unlikely to halt the firm’s commercial advance for long.

Overall, there is a huge shadow world of out-sourced businesses. They include firms like Serco, Capita, Interserve, Sodexo, and the Compass Group. As the journalist John Harris comments: ‘their names seem anonymously stylised, in keeping with the sense that they seemed both omni-present, and barely known’.9 Their non-executive directors often serve on the board of more than one firm at a time, linking them in an emergent international contractocracy. Collectively, they constitute a powerful vested interest.

Where will it end? The current system is killing representative democracy. Elected ministers and councillors find themselves in charge of dwindling bureaucracies. So much the better, cry some. But quis custodiet? The current system is not properly accountable. It is especially dangerous when private firms are taking over the regulatory functions, which need the guarantee of impartiality. (More on that point in a later BLOG). Successful states need efficient bureaucracies, that are meritocratic, impartial, non-corrupt, flexible, and answerable regularly (and not just at contract-awarding intervals) to political scrutiny. The boundaries between what should be state-provided and what should be commercially-provided are always open to political debate. But, given that the state often funds and ultimately guarantees many functions, its interest in what is going on in its name cannot be abrogated.

The outcome will not be the same as the French Revolution, because history does not repeat itself exactly. Indeed, the trend nowadays is towards contracting-out rather than the reverse. Yet nothing is fixed in stone. Wearing my long-term hat, I prophecy that eventually many of the profit-motive ‘Service Farmers’ will have to go, rejected by democratic citizens, just as the ‘Tax Farmers’ went before them.

1 Patrick Cosgrave, ‘Obituary: Lord Ridley of Liddesdale’, Independent, 6 March 1993.

2 Another term for this minimal-government philosophy is ‘Minarchism’ or limited government libertarianism, often associated with free-marketry. Minarchism should be distinguished from anarchism or no-government, which has different ideological roots.

3 ‘To be attached to the subdivision, to love the little platoon we belong to in society, is the first principle (the germ as it were) of public affections. It is the first link in the series by which we proceed towards a love to our country and to mankind’: E. Burke, Reflections upon the Revolution in France (1790), ed. C.C. O’Brien (Harmondsworth, 1969), p. 135.

4 E.N. White, ‘From Privatised to Government-Administered Tax-Collection: Tax Farming in Eighteenth-Century France’, Economic History Review, 57 (2004), pp. 636-63.

5 Reported in Event, 14 Feb. 2013.

6 Daily Mail, 21 May 2013, from Mail-online: www.dailymail.co.uk, viewed 9 Aug. 2013.

7 See ‘Who we are’ in website www.g4s.com.

8 Daily Telegraph, 6 August 2013, from Telegraph-online: www.telegraph.co.uk, viewed on 9 Aug. 2013.

9 John Harris on Serco, ‘The Biggest Company you’ve never heard of’, Guardian, 30 July 2013: supplement, pp. 6-9.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 33 please click here

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide.

Matching images to script: People in general express great appreciation of the visuals within the DVD. Credit here goes especially to the picture research of graphic designer Suzanne Perkins and to the film research of the producer/director Mike Marchant. Together they found masses of previously unknown material. Brilliant. It’s a great encouragement for researchers to realise exactly how much remains to be discovered (or sometimes rediscovered) in local archives and film libraries. Visual material is now getting a proper share of attention, transforming how history can be presented. That’s now being taken for granted, although there are still some bastions to fall before the incoming tide. On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’.

On the other hand, it’s very good to show a striking image just before it’s mentioned in the script. Then as the narrator stresses something or other, viewers share a sense of realisation. Whereas if the images follow just too late, the reverse effect is achieved. Viewers feel slightly insulted: ‘why are you showing me an XXX now, I already know that, because the narrator has just told me’. But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort.

But very hard work. If I’d known at the start what it all entailed, I’d have declined to take on the octopus task of script-writing, co-directing, and organising lots of other people. Especially as I was doing all this in my so-called spare time, as a busy academic historian. Not that I can complain about the Battersea comrades, who shared in the research, the editing, the performances and the design of the DVD cover and publicity. The voices on the DVD are all those of local activists and residents, led by the celebrated actors Tim West and Prunella Scales. One and all were positive and very patient, during the 18 months of protracted effort. The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends).

The third and final point relates to the challenge of bringing a historical script up until the present day, without making the conclusion too dated. I decided to make the narrative gradually speed up, with a more leisurely style for the exciting early years and a more staccato survey of the later twentieth century. That manoeuvre was devised to generate narrative drive. But one result was that various sections had to be axed, late in the day. Hence one serious criticism was that the role of pioneering women in Battersea Labour Party, which had appeared in the first Powerpoint lecture, was cut from the DVD. It was a shame but artistically necessary, because too long a retrospective review undermined the narrative momentum. (With the later resources of my website, I could have published the entire script, including axed sections, as a way of making amends). Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =

Copies of the DVD Red Battersea, 1908-2008 are obtainable for £5.00 (in plastic cover) from Tony Belton =

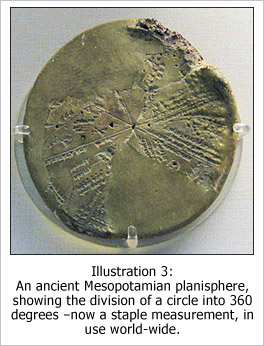

The second recommendation links with the first. We should define the subject as the study not of the ‘dead past’ but of ‘living history’.

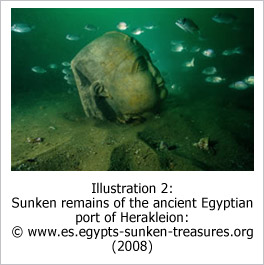

The second recommendation links with the first. We should define the subject as the study not of the ‘dead past’ but of ‘living history’. On the other hand, while some elements of history are ‘lost’, past cultures are not necessarily inaccessible to later study. Just as travellers can make an effort to understand foreign countries, so historians and archaeologists have found many ingenious ways to analyse the ‘dead past’.

On the other hand, while some elements of history are ‘lost’, past cultures are not necessarily inaccessible to later study. Just as travellers can make an effort to understand foreign countries, so historians and archaeologists have found many ingenious ways to analyse the ‘dead past’. So there is an alternative quotation of choice for those who stress the connectivity of past and present. It too comes from a novelist, this time from the American Deep South, who was preoccupied by the legacies of history. William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun (1951) made famous his dictum that:

So there is an alternative quotation of choice for those who stress the connectivity of past and present. It too comes from a novelist, this time from the American Deep South, who was preoccupied by the legacies of history. William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun (1951) made famous his dictum that: By the way, so notorious has that advertisement become that it is strangely difficult to find the originals image on the web. It seems to have been self-censored by both the Museum and the ad agency – probably in shame.

By the way, so notorious has that advertisement become that it is strangely difficult to find the originals image on the web. It seems to have been self-censored by both the Museum and the ad agency – probably in shame. Why then has the subject matter of History been comparatively undervalued in recent years? It can’t just be the power of the Skills agenda and the influence of ministers fussing about every subject’s contribution to the economy.

Why then has the subject matter of History been comparatively undervalued in recent years? It can’t just be the power of the Skills agenda and the influence of ministers fussing about every subject’s contribution to the economy.