MONTHLY BLOG 88, HOW I WRITE AS A HISTORIAN

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2018)

Invited by Buff-Coat to comment on how I compose works of history,

the answer fell into nine headings,

written as reminders to myself: 1

- Learn to enjoy writing: writing is a craft skill, which can be improved with regular practice.2 Learn to enjoy it.3 Bored authors write bored prose. Think carefully about your intended readership, redrafting as you go. Then ask a trusted and stringent critic for a frank assessment. Adjust in the light of critical review – or, if not accepting the critique, clarify/strengthen your original case.4

- Have something to say: essential to have a basic message, conferring a vital spark of originality for every assignment.5 Otherwise, don’t bother. But the full interlocking details of the message will emerge only in course of writing. So it’s ok to begin with working titles for books/chapters/essays/sections and then to finalise them about three-quarters of way through writing process.

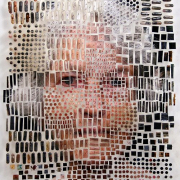

- Start with mind-mapping: cudgel brains and think laterally to provide visual overview of all possible aspects of the topic, including themes, debates and sources. This is a good moment for surprise, new thoughts. From that, generate a linear plan, whilst keeping mind-map to hand as reference point. And it’s fine, often essential, to adapt linear plan as writing evolves. As part of starting process, define key terms, to be defined at relevant point in the text.6

|

Idea of a Mind-Map |

- Blend discussion of secondary literature seamlessly into analysis: beginners are rightly trained to start with a discrete historiographical survey but, with experience, it’s good to blend exposition into the analysis as it unfolds. Keep readers aware throughout that historians don’t operate in vacuum but debate constantly with fellow historians in their own and previous generations. It’s a process not just of ‘dialogue’ but of complex ‘plurilogue’.7

- Interpret primary sources with respect and accuracy: evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of primary sources from the past; be prepared to interpret them but only while treating them with the utmost respect and accuracy. Falsifying data, misquoting sources, or hiding unfavourable evidence are supreme academic sins. Historians are accustomed to write within the constraints of the evidence.8 That’s their essential discipline. Hence the claim by postmodernist theorists that historians can invent (or uninvent) the past just as they please is not justified. Indeed, if history (the past) was simply ‘what historians write’, there’d be no way of evaluating whether one historian’s arguments are historically more convincing than another’s. And there’d be no means of rebutting (say) Holocaust denial.9 The challenging task of evaluating, interpreting and knitting together many different forms of evidence from the past, in the light of evolving debates, is the essence of the historian’s practice.10

- Expound your case with light and shade: Counteract the risk of monotony by incorporating variety. Can take the form of illustrations; anecdotes; even jokes. Vary choice of words and phrases.11 Vary sentence lengths. Don’t provide typical academic prose, full of lengthy sentences, stuffed with meandering sub-clauses, all written in densely Latinate terminology. But don’t go to other extreme of all rat-a-tat sub-Hemingway terse Anglo-Saxon texts either. Variety keeps readers interested and gives momentum to an unfolding analysis.

- Know the arguments against your own: advocacy works best not by caricaturing opposite views but by understanding them, in order to refute them successfully. All courtroom lawyers and politicians are well advised to follow this rule too. But no need to focus exclusively on all-out attack against rival views. That way risks making your work become dated, as the debates change.

- Relate the big arguments to your general philosophy of history:12 Don’t know what that is? Time to decide.13 If not your lifetime verdict, then at least an interim assessment. Clarify as the analysis unfolds. But again ensure that the general philosophy is shown as informing the unfolding arguments/evidence. It’s not an excuse for suddenly inserting a pre-conceived view.

- Know how to end:14 Draw threads together and end with a snappy dictum.15

ENDNOTES:

1 This BLOG is the annotated text of a brief report, first posted on 15/03/2018 on: http://keith-perspective.blogspot.co.uk/2018/03/how-i-write-as-historian-by-penelope-j.html, with warm thanks to Keith Livesey, alias Buff-Coat, for the invitation.

2 See P.J. Corfield, Coping with Writer’s Block (BLOG/34, Oct. 2013), on website: https://www.penelopejcorfield.com/monthly-blogs/. All other PJC BLOGS cited in the following endnotes can be consulted via this website.

3 Two different historians who influenced me had very distinctive messages and writing styles: see P.J. Corfield, Two Historians who Influenced Me (BLOG/15, Dec. 2011).

4 P.J. Corfield, Responding to Anonymous Academic Assessments (BLOG/81, Sept. 2017). It followed idem, Writing Anonymous Academic Assessments (BLOG/80, Aug. 2017).

5 History is such a vital subject for all humans that it’s hard not to find something to say. See P.J. Corfield, All People are Living Histories, which is Why History Matters. A Conversation Piece for Those who Ask: Why Study History? (2007), available on the Making History website of London University’s Institute of Historical Research: www.history.ac.uk/makinghistory/resources/articles/why_history_matters; and also on PJC personal website: www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk: Essays on What is History? Pdf/1.

6 That advice includes avoiding terms still widely used by others, like racial divisions between humans. They are misleading and based on pseudo-science. See P.J. Corfield, Talking of Language, It’s Time to Update the Language of Race (BLOG/36, Dec. 2013); idem, How do People Respond to Eliminating the Language of ‘Race’? (BLOG/37, Jan.2014); and idem, Why is the Language of ‘Race’ Holding On for So Long, when it’s Based on a Pseudo-Science? (BLOG/38, Feb. 2014).

7 P.J. Corfield, Does the Study of History ‘Progress’ and How does Plurilogue Help? (BLOG/61, Jan. 2016).

8 P.J. Corfield, What’s So Great about Historical Evidence? (BLOG/66, June 2016); idem, What Next? Interrogating Historical Evidence (BLOG/67, July 2016).

9 For further discussion, see P.J. Corfield, ‘Time and the Historians in the Age of Relativity’, in A.C.T. Geppert and T. Kössler (eds), Obsession der Gegenwart: Zeit im 20. Jahrhundert; transl. as Obsession with the Here-and-Now: Concepts of Time in the Twentieth Century, in series Geschichte und Gesellschaft: Sonderheft, 25 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2015), pp. 71-91. Also posted on PJC website: www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk: Essays on What is History? Pdf/38.

10 On the need to differentiate between facts and pseudo-facts, see P.J. Corfield, Facts and Factoids in History (BLOG/52, April 2015).

11 And at times, new words are needed: see P.J Corfield, Inventing Words (BLOG/84, Dec. 2017); and idem, Working with Words (BLOG/85, Jan. 2018).

12 My own account of historical trialectics is available in P.J. Corfield, Time and the Shape of History (Yale University Press, 2007). It’s also expounded theme by theme in idem, Why is the Formidable Power of Continuity So Often Overlooked? (BLOG/2. Nov. 2010); idem, On the Subtle Power of Gradualism (BLOG/4, Jan. 2011); and idem, Reconsidering Revolutions (BLOG/6, March 2011). And further discussed in idem, ‘Teaching History’s Big Pictures, Including Continuity as well as Change’, Teaching History: Journal of the Historical Association, no. 136 (2009), posted on PJC personal website: www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk: Essays on What is History? Pdf/3.

13 The time to decide for yourself might not correspond with interest from others. Never mind! Stick to your guns. See also P.J. Corfield, Writing into Silence about Time (BLOG/73, Jan. 2017); idem, Why Can’t we Think about Space without Time? (BLOG/74, Feb. 2017); idem, Humans as Time-Specific Stardust (BLOG/75, March 2017); and idem, Humans as Collective Time-Travellers (BLOG/76, April 2017).

14 It’s much easier to advise and/or to supervise others: see P.J. Corfield, Supervising a Big Research Project to End Well and On Time: Three Framework Rules (BLOG/59, Nov. 2015); idem, Writing Through a big Research Project: Not Writing Up (BLOG/60, Dec. 2015).

15 On my own travails, see P.J. Corfield, Completing a Big Project (BLOG/86, Feb.2018); and idem, Burned Boats (BLOG/87, March 2018).

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 88 please click here